Monkeypox: Causes, Prevention, Treatment Vaccination

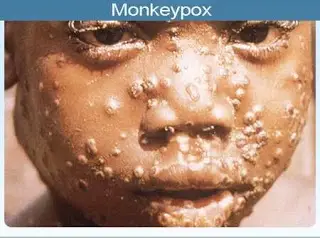

Monkeypox is a viral disease that produces pox lesions on the skin and is closely related to smallpox but is not nearly as deadly as smallpox was.

The history of monkeypox is new (1958), and the first human cases were diagnosed and differentiated from smallpox in the early 1970s.

Monkeypox virus causes monkeypox. The majority of cases are transmitted from animals (rodents) to humans by direct contact. Person-to-person transfer, probably by droplets, can occur infrequently.

Risk factors for monkeypox include close association with African animals (usual rodents) that have the disease or caring for a patient who has monkeypox.

During the first few days, symptoms are nonspecific and include fever, nausea, and malaise. After about four to seven days, lesions (pustules, papules) develop on the face and trunk that ulcerate, crust over, and begin to clear up after about 14-21 days, and lymph nodes enlarge. There may be some scarring.

The diagnosis of monkeypox is often made presumptively in Africa by the patient’s history and the exam that shows the pox lesions, however, a definitive diagnosis is made by PCR, ELISA, or Western blotting tests that are usually done by the CDC or some state labs. Definitive diagnosis is important to rule out other possible infectious agents like smallpox.

Treatment may consist of immediate vaccination with smallpox vaccine because monkeypox is so closely related to smallpox. Treatment with an antiviral drug or human immune globulin has been done.

In general, the prognosis for monkeypox is good to excellent as most patients recover. The prognosis may decrease in immunocompromised patients, and patients with other problems such as malnutrition or lung disease may have a poorer prognosis.

Monkeypox is preventable as long as people avoid direct contact with infected animals and people. Vaccination against smallpox seems to afford about an 85% chance of avoiding the infection. There is no commercially available vaccine specifically for monkeypox.

Research is ongoing to study antivirals, genetics, and rapid tests for monkeypox.

What causes monkeypox? How is monkeypox transmitted?

Monkeypox is caused by an Orthopoxvirus named monkeypox. The viruses are oval brick-shaped viruses that have a lipoprotein layer with tubules or filaments that cover the viral DNA. There are many members of this viral genus, including such species as variola (smallpox), cowpox, buffalopox, camelpox, rabbitpox, and others. Most species infect a particular animal species but occasionally may infect other mammals.

Monkeypox virus, brick-shaped negative stained virus grown in tissue cultures, visualized by electron microscopy

Transmission of monkeypox is usually by direct contact with infected animals or possibly by eating poorly cooked meat from an infected rodent or monkey. Cutaneous or mucosal lesions on the infected animals are a likely source of transmission to humans, especially when the human skin is broken due to bites, scratches, or other trauma — are a likely source for virus infection. Person-to-person transfer, probably by infected respiratory droplets, is possible but is not often documented. One study suggested that only about 8%-15% of infections were transmitted person to person among close family members.

Monkeypox Signs and Symptoms

The first symptoms that occur are:

- nonspecific — fever,

- sweating,

- malaise and some patients may develop a cough,

- nausea, and shortness of breath.

About two to four days after a fever develops, a rash with papules and pustules develops most often on the face and chest, but other body areas may eventually be affected, including mucous membranes inside the nose and mouth. These skin and mucous membrane pox lesions can ulcerate, crust over, and then begin to heal in about 14-21 days. In addition, lymph nodes usually swell during this time. Some pox lesions may become necrotic and destroy sebaceous glands, leaving a depression or pox scar that, with monkeypox, may gradually become less pronounced over a few years. The toxemia that was seen with smallpox is not seen with monkeypox.

Is it possible to prevent monkeypox?

Monkeypox can be prevented by avoiding eating or touching animals known to acquire the virus in the wild (mainly African rodents and monkeys). The person-to-person transfer has been documented. Patients who have the disease should physically isolate themselves until all of the pox lesions have healed (lost their crusts), and people who are caring for these patients should use barriers (gloves and face masks) to avoid any direct or droplet contact. Caregivers should obtain a smallpox vaccination (see below).

Because smallpox and monkeypox are so closely related, studies have suggested that people vaccinated against smallpox have about an 85% chance of being protected from monkeypox. Consequently, the CDC recommends the following:

Patients with depressed immune systems and those who are allergic to latex or smallpox vaccine should not get the smallpox vaccine.

Anyone else who has been exposed to monkeypox in the past 14 days should get the smallpox vaccine, including children under 1 year of age, pregnant women, and people with skin conditions.

There is no commercially available vaccine designed specifically for monkeypox.

What is the treatment for monkeypox?

The CDC recommends the following:

- A smallpox vaccination should be administered within two weeks of exposure to monkeypox.

- Cidofovir (Vistide), an antiviral drug, is suggested for patients with severe, life-threatening symptoms.

- Vaccinia immune globulin may be used, but the efficacy of use has not been documented.

For severe symptoms, supportive measures such as mechanical ventilation may rarely be needed. Consultation with an infectious-diseases expert and the CDC is recommended.

Credit Source

- Medicinenet- monkeypox